hạt | tim

2016

duo by Lê Hiền Minh & Cam Xanh

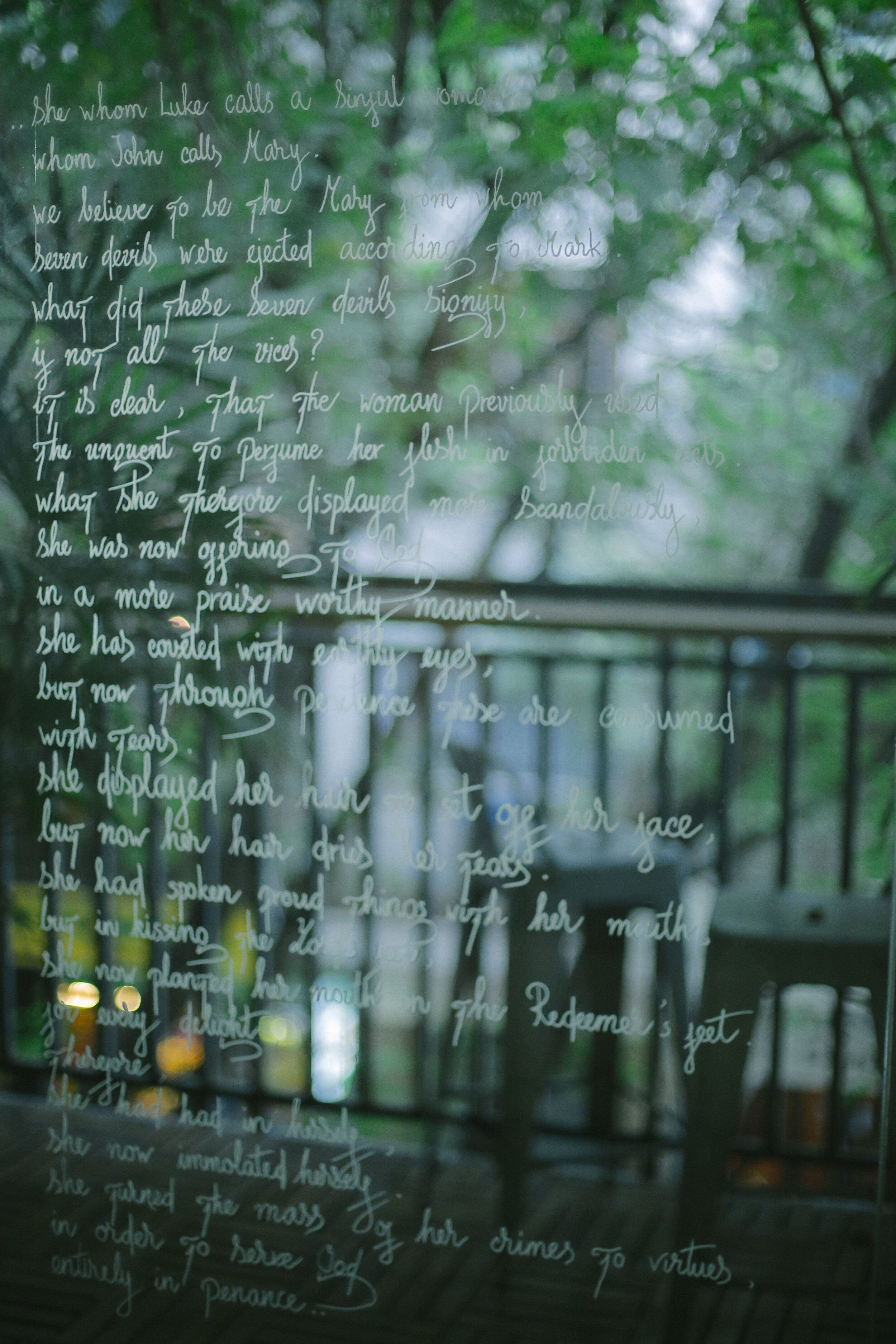

“she whom Luke calls the sinful woman,

whom John calls Mary,

we believe to be the Mary from whom

seven devils were ejected according to Mark. what did these seven devils signify,

if not all the vices?

It is clear, that the woman previously used

the unguent to perfume her flesh in forbidden acts.

what she therefore displayed more scandalously, she was now offering to God

in a more praise worthy manner.

she had coveted with earthly eyes,

but now through penitence these are consumed with tears.

she displayed her hair to set off her face,

but now her hair dries her tears.

she had spoken proud things with her mouth,

but in kissing the Lord’s feet,

she now planted her mouth on the Redeemer’s feet.

for every delight, therefore,

she had had in herself, she now immolated herself. .

she turned the mass of her crimes to virtues,

in order to serve God entirely

in penance..” - Pope Gregory the Great (homily XXXIII)

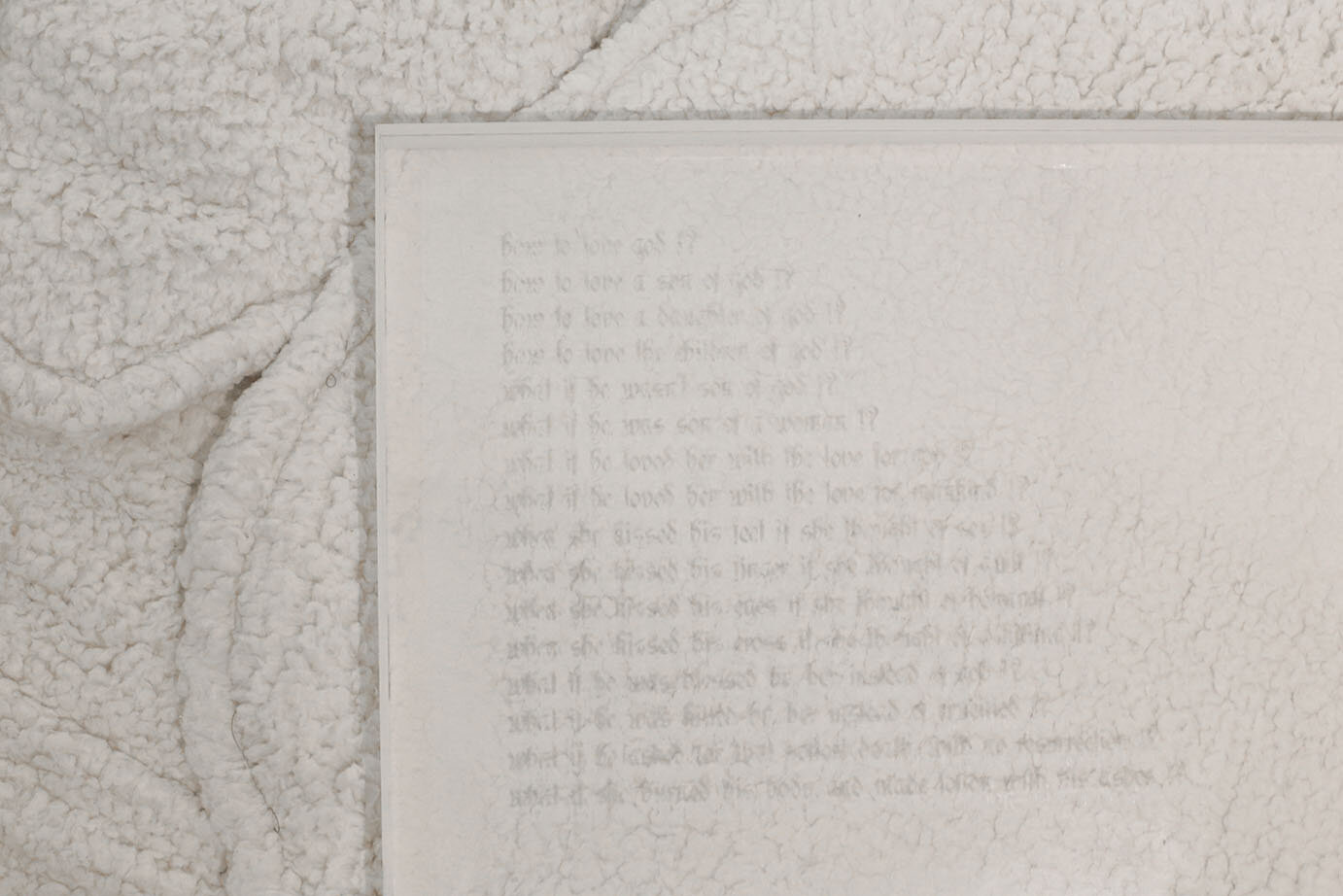

how to love god!?

how to love a son of god!?

how to love a daughter of god!?

how to love the children of god!?

what if he wasn’t son of god!?

what if he was son of a woman!?

what if he loved her with the love for god!?

what if he loved her with the love for mankind!?

when she kissed his feet if she thought of sex!?

when she kissed his finger if she thought of guilt!?

when she kissed his eyes if she thought of betrayal!?

when she kissed his cross if she thought of a killing!?

what if he was blessed by her instead of god!?

what if he was killed by her instead of crucified!?

what if he asked for that softest death, with no resurrection!?

what if she burned his body and made lotion with his ashes!?

..

hey, women!

here is the vitality of beauty

here is the secret of youth

here is the magic of love

she offers the silky skin

she offers immortality

she offers his flesh, his bone, his blood, his heart, his soul, his life.. his godless love

...

she could smell the roses on your bodies

she could touch your goddess skins

she could feel his life running in your veins

she could see him in your hearts

then she knows how to love the children of god

then she knows how to love a daughter of god

then she knows how to love a son of god

then she knows she will be crucified

for mankind.. resurrection, reproduction

.. or forgiveness!?

and so she thinks of the killing

and so it smiles, her commercial heart...

what if he asked...

none stop thinking..what if he asked...

so it’s smiling, the commercial heart...

a commercial heart and the woman from Magdala.. or, an obituary of a mortal man

< Cam Xanh, 2014 >

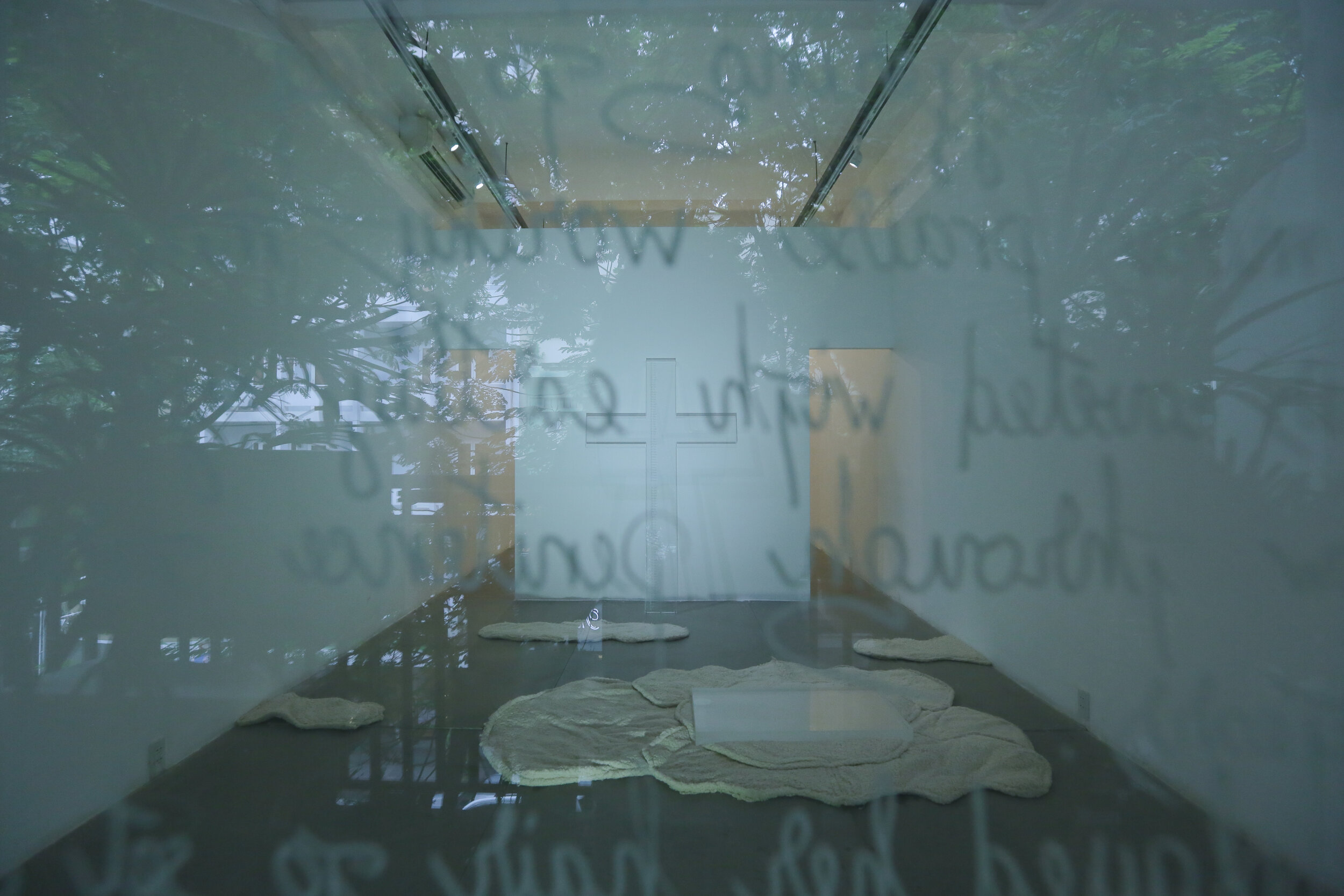

Le Hien Minh and Cam Xanh’s duo installation take place in two neighboring rooms, each of which presents a different altar. Cam Xanh constructs a scene with a lone cross and Hien Minh, a Northern Vietnamese altar. No recognizable saints, ancestors or incense is in sight. The two artists’ attitude towards the conventional fixtures of worship departs from veneration and slides towards playfulness.

Hien Minh’s “balls” (or “hạt” in Vietnamese, the title of her work) are made from Vietnam- ese traditional Dó paper, which she crumples into shriveled little spheres. Dyed with pig- ment, these seemingly innocuous pickled-plum-like balls evoke a wrinkled and stale image of masculine pride. Hien Minh’s ball-filled jar parodies the “rượu thuốc” (medicinal liquor) jar commonly found in many Vietnamese males’ living room. Liquor made with animal parts like cobra heads or tiger testicles is traditionally believed to be a powerful organic Viagra for men. Though made by distilling dead beings, a method considered ghastly by some, medic- inal liquor is highly regarded as an effective supplement of masculinity. Hien Minh looks at the eerie implication of masculinity, and her work explores what vanity and virility might look like to an observer of the patriarchy in Vietnam. The sheer number of hand-sculpted balls (numbering over 20,000) creates a scene of overwhelming abundance and power. Beyond gender, viewers are invited to meditate on the private process of the artistic maker and the astonishing amount of labor and time behind each work of art.

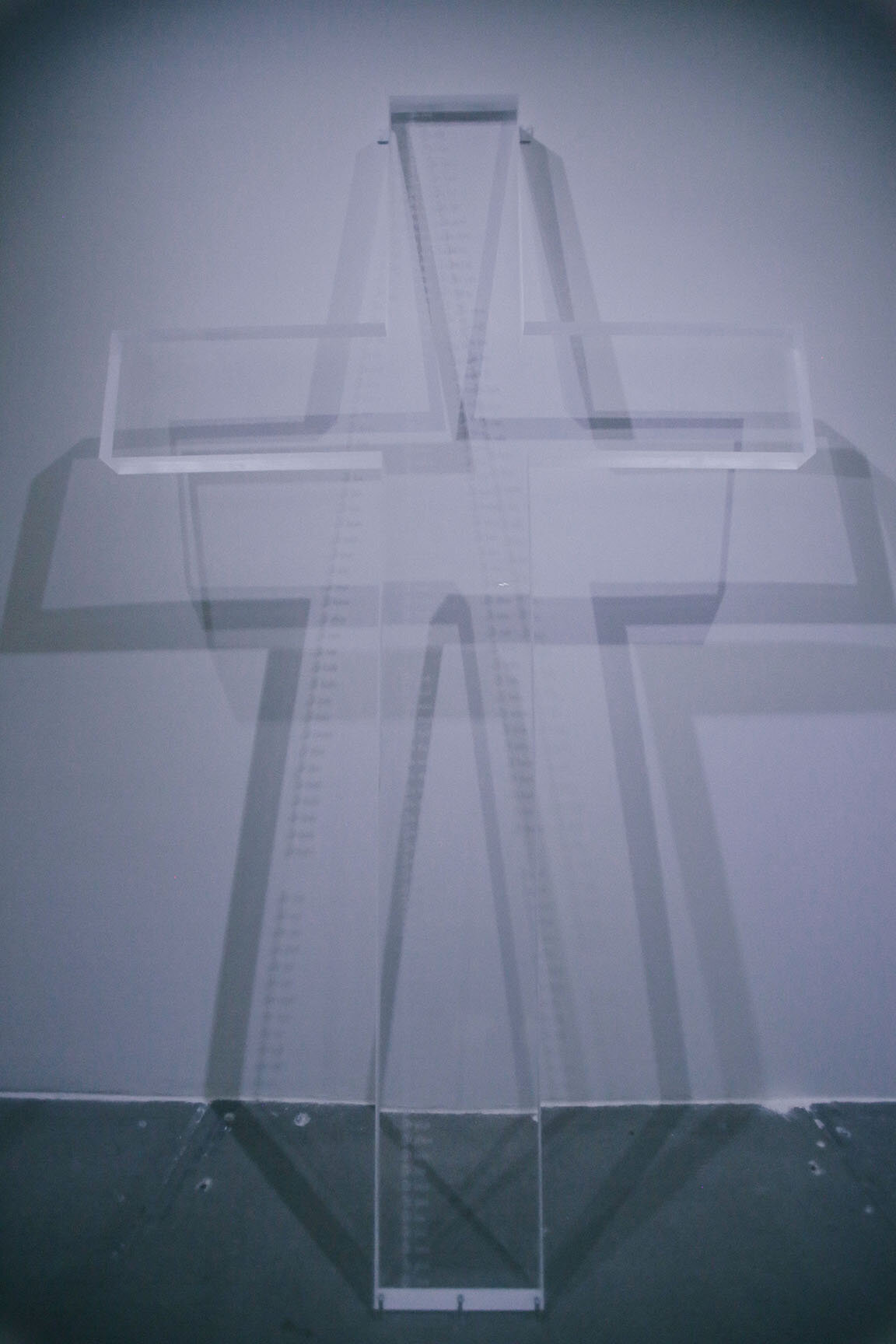

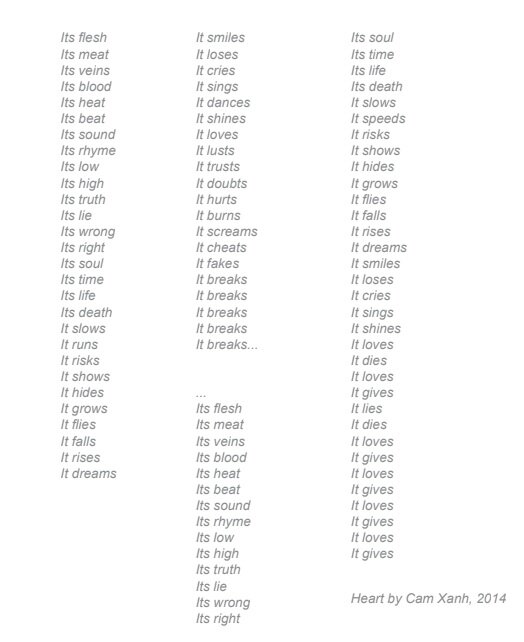

In the room next door, Cam Xanh unsettles Christian history by playing with form and lan- guage in her installation Tim (the Vietnamese word for ‘heart’). Her objects are minimalist - a human-sized cross and a prayer table, both made of plexiglass. There is no bible. The only texts to be seen are poems ethereally suspended between the layers of plexiglass along the cross and table surface. The rhythmic quality of Cam Xanh’s poetry, together with cloud-like patches of sheepskin scattered across the floor, fill the godless room with strange comfort. But in other ways, her plexiglass chapel remains inscrutable. Lines from her poem describe a fictional ending of the love story between the Son of God and Mary Magdalene (or the woman from Magdala in old Palestinian). The love affair which is not discussed in the Gospels has now been highlighted as the main act. In this reinvented “Last Temptation of Christ” episode, the artist switches the roles of the martyr and the disciple, envisioning a new religion in which love is disseminated in the form of stem-cells.

These two artists’ altars are atypical as they are not about reverence but liberation from the revered. Cam Xanh fabricates bold fictions on the identity of the martyred, while Hien Minh makes an altar against constructed masculinity. By re-examining and reinventing religious objects such as the acrylic glass cross or the altar brimming with paper balls, the artists pose unnerving questions about who and what has been idolized and venerated throughout history. Their altars both insinuate and destabilize the ideologies behind human devotion.

< Quyen Nguyen >

The glass jar is used to infuse traditional herbs with rice liquor to make herbal spirits. Many older Vietnamese men will have a jar of herbal spirits in their home because it is widely believed to be good for men’s sexual health. The lacquer table is a Northern style altar. An altar like this would exist in a typical home, and is used to display images of ancestors. It is also the place to put an incense holder, which Vietnamese believe house the souls of their ancestors.

The jar and the lacquer table are familiar objects to Vietnamese. The Balls on the other hand are completely foreign objects, despite the fact they are made from Vietnam’s traditional handmade Dó paper.

Vietnamese women struggle to find a balance between traditional and modern notions of success. Traditionally, a woman’s success is defined by the success of her husband and the success of her son. This ideal has been passed down through the generations by our ancestors and is a heavy burden to many Vietnamese women. The modern successful woman, is one who has the freedom to choose her own path and is defined by her own success, not by the success of men she is associated with. This idea of a modern woman is a foreign concept in Vietnamese society, yet it is influencing women who desire more than what the traditional roles offer, and it is steadily becoming part of our culture, despite our traditions.

< Le Hien Minh >

The title “Hạt | Tim,” is comprised of Vietnamese words that translate to English as “balls/ heart,” evoking a juxtaposition of sexual and romantic love—or lust and spiritual purity. In the case of Hiền Minh’s installation Balls (2004), its connection to the exhibition title is quite literal, given that the piece consists of more than 20,000 balls of paper. The balls are made from traditional Vietnamese hand-made paper, dyed red using natural pigments. The work delivers an uncanny jolt when encountered in the front room of Dia’s sleek space, mostly due to the staggering number of balls, but also because the table that they are set on is one that is typically encountered in Vietnamese homes, and not gallery spaces. Such altar tables usually feature incense burners and photos of deceased elders, but for her work, the artist has supplanted these traditional items with a glass jar full of paper balls, as well as many others balls piled upon the altar’s surface and thousands more on the floor.

As the press release explains: “Hiền Minh’s ball-filled jar parodies the ‘ruou thuoc’ (medicinal liquor) jar commonly found in many Vietnamese males’ living room. Liquor made with animal parts like cobra’s heads or tiger testicles is traditionally believed to be a powerful organic Viagra for men.” By installing an over-abundance of phallocentric symbols in the place of highest reverence within the Vietnamese home, Hiền Minh hints at the ways in which certain traditional values may serve one gender at the expense of the other.

While Hạt is situated squarely within a traditionally Vietnamese milieu, Cam Xanh’s Tim, ex- pressed through the work The Seven Capital Sins – The Perfect Love (2015–16), engages with Christian iconography, which makes a logical compliment to Hạt, since Catholicism is the second most popular religion in Vietnam. The most striking element of this installation is the Plexiglas cross embossed with poetry, which, despite its airy, transparent appearance, weighs more than 200 kilograms, achieving a sense of tension—between elements of min- imalism and excess—that parallels that of Hiền Minh’s work. Another rectangular, tomb- stone-like Plexiglas piece is on the floor, a positioning that forces one to stoop down to read the poems inscribed on it, which causes the amusing effect of making viewers inadvertently kneel before the cross as if in genuflection.

Cam Xanh’s Plexiglas tablet lies on a pile of sheepskins, which makes a nice cushion for the viewers’ knees, but the comforting vibe is undercut by the fact that the pelts are nailed to the floor, reminding one of the crucifixion. The inscribed poems recast the relationship between Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene as an equal one between lovers, in which she does not succumb to his love any more than he does to hers. However, such sentiments are kept in check by a biblical quote painted on the back window of the gallery space, in which Mary Magdalene is reviled for her sins. In this manner Xanh suggests that, although men and women should be considered equal partners in love and sin, the dominant narrative of Chris- tianity places the burden of guilt on the woman to protect the purity of its male savior—a historical injustice that helps to perpetuate sexual inequality to this day.

by Dave Willis on Art Asia Pacific Magazine, 2016